Category: Technology

Apple is reportedly planning to launch AI-powered glasses, a pendant, and AirPods

Apple is pushing ahead with plans to launch its first pair of smart glasses, along with an AI-powered pendant and camera-equipped AirPods, according to a report from Bloomberg’s Mark Gurman. The three devices come with built-in cameras and will connect to the iPhone, allowing Siri to use “visual context to carry out actions,” Bloomberg reports. […]

Waymo Is Getting DoorDashers to Close Doors on Self Driving Cars

The companies have launched a pilot program in Atlanta, where “during the rare event a vehicle door is left ajar, preventing the car from departing, nearby Dashers are notified, allowing Waymo to get its vehicles back on the road quickly.”

The insect-inspired bionic eye that sees, smells and guides robots

The compound eyes of the humble fruit fly are a marvel of nature. They are wide-angle and can process visual information several times faster than the human eye. Inspired by this biological masterpiece, researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences have developed an insect-scale compound eye that can both see and smell, potentially improving how drones and robots navigate complex environments and avoid obstacles.

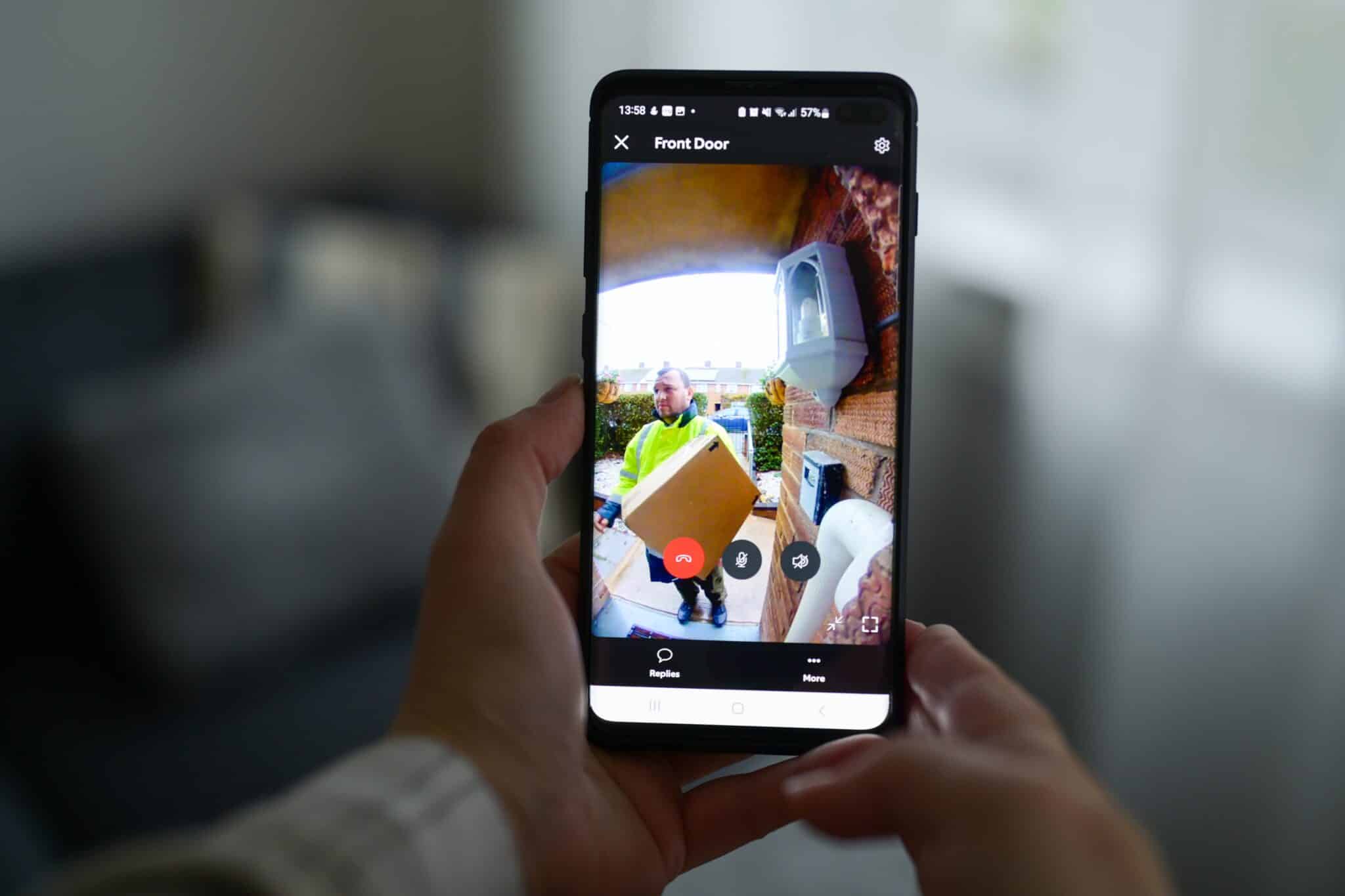

Ring Super Bowl ad sparks backlash over AI camera surveillance

A Super Bowl commercial for Amazon’s Ring doorbell camera triggered swift backlash, with critics arguing that the company used an emotional story about a lost dog to promote a neighborhood scale camera network while minimizing the broader privacy and civil liberties implications of searchable AI video.

The short commercial which was intended to highlight lost pet reunions instead ignited a broader national conversation about how much machine vision society is willing to accept in exchange for safety and convenience.

The ad highlighted Ring’s Search Party feature, which is designed to help reunite owners with lost dogs by using AI to scan video from nearby participating cameras for potential matches.

In the commercial, a missing pet is located through coordinated alerts across a network of doorbell and outdoor cameras. But what Ring framed as a story of community assistance was viewed by many privacy advocates as a normalization of ambient surveillance infrastructure.

Civil liberties groups said the ad blurred the line between voluntary home security and de facto neighborhood monitoring. They warned that packaging AI powered video search as a feel-good service during one of the most watched television events of the year risks desensitizing viewers to how such systems function at scale.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) issued one of the strongest responses. “Amazon Ring’s Super Bowl ad offered a vision of our streets that should leave every person unsettled about the company’s goals for disintegrating our privacy in public,” the organization said.

EFF added that the commercial, “disguised as a heartfelt effort to reunite the lost dogs of the country with their innocent owners, previewed future surveillance of our streets, a world where biometric identification could be unleashed from consumer devices to identify, track, and locate anything, human, pet, and otherwise.”

Sen. Ed Markey, a longtime critic of consumer surveillance technologies, also condemned the ad. He said Ring is “turning your neighborhood into a surveillance network,” and warned that tools marketed as community safety features can “create serious risks for privacy and civil liberties.”

In prior oversight letters examining Ring’s practices, Markey has argued that “Americans should not have to trade their privacy for security.”

Search Party allows users to create a lost dog post within the Ring app and activate AI scanning among participating nearby cameras. The system analyzes footage for potential matches based on characteristics such as size, breed, and markings.

If a possible match is detected, the camera owner receives a notification and can choose whether to share the clip. Ring has described the feature as voluntary and time limited, emphasizing that no footage is automatically sent to the pet owner without user approval.

Company executives have pointed to early reunions as evidence that the feature works and say it simply streamlines what neighbors already do when they share lost pet posts through social media and community forums.

Supporters argue that participation is optional and that users retain control over their own footage.

Critics counter that the backlash is not about dogs but about infrastructure. They argue that a distributed network of privately owned cameras equipped with AI search capabilities normalizes constant monitoring.

Even if the feature is limited to pets, they say the technical foundation resembles systems used for object recognition and biometric identification. In that context, the difference between identifying a dog and identifying a person becomes a question of software configuration rather than hardware capability.

Another flashpoint involves default participation. During rollout, the feature was enabled by default on certain compatible devices, requiring users to opt out if they did not want their cameras to participate.

Privacy advocates argue that default settings shape real world surveillance reach because many users do not regularly review device configurations. They contend that opt out architecture can quietly scale a searchable network across entire neighborhoods.

The Super Bowl ad also aired amid broader debate over Ring’s expanding AI features, including tools that allow users to identify familiar faces and receive personalized alerts.

Last October, Markey sent a letter to Amazon CEO Andrew Jassy in which warned that the company’s new Familiar Faces feature represents a dangerous step toward normalizing mass surveillance in American neighborhoods.

Markey described the rollout as “a dramatic expansion of surveillance technology” that poses “vast new privacy and civil liberties risks,” arguing that ordinary people should not have to fear being tracked or recorded when walking past a home equipped with a Ring camera.

While the Search Party feature is not marketed as a facial recognition system, critics argue that the same classification infrastructure underpins both types of capabilities and makes future expansion easier.

Concerns about law enforcement access resurfaced as well. Ring previously ended a program that facilitated direct police requests for footage through its app, but it continues to operate community request tools that allow public safety agencies to ask nearby users to voluntarily share video tied to investigations.

Those requests are integrated into platforms used by public safety technology vendors, including Flock Safety, which operates automated license plate reader networks.

Privacy advocates argue that once footage is shared with local agencies, it can be retained, combined with other datasets, or disseminated further in ways that are difficult for individual users to track.

Even if Ring does not provide direct backend access to federal agencies, they say downstream sharing arrangements create uncertainty about how footage ultimately circulates.

Some social media speculation during the controversy claimed that federal immigration authorities could directly access Ring cameras. Ring has denied giving Immigration and Customs Enforcement direct access to its video feeds or systems.

Civil liberties groups maintain that the broader concern is structural rather than agency specific. Once a searchable neighborhood camera network exists, they argue, questions of governance and oversight extend beyond any single policy assurance.

At the center of the debate is a larger cultural tension. The Super Bowl ad presented AI driven monitoring as reassuring and community minded. Critics say that framing risks redefining constant observation as a civic virtue. Supporters say the feature represents practical innovation that helps solve everyday problems.

The episode illustrates how rapidly consumer camera technology is converging with capabilities once associated primarily with state surveillance. As AI makes video archives searchable and classifiable at scale, the boundary between smart home convenience and neighborhood intelligence infrastructure continues to narrow.

Free Tool Says it Can Bypass Discord’s Age Verification Check With a 3D Model

The tool presents users with a 3D model they can then manipulate to, the creator says, bypass Discord’s age verification system.

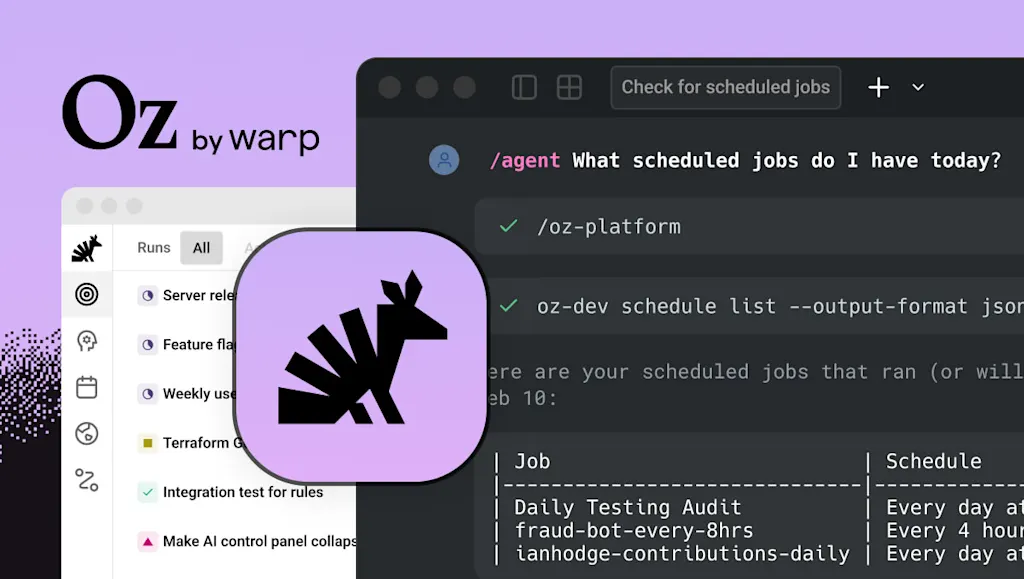

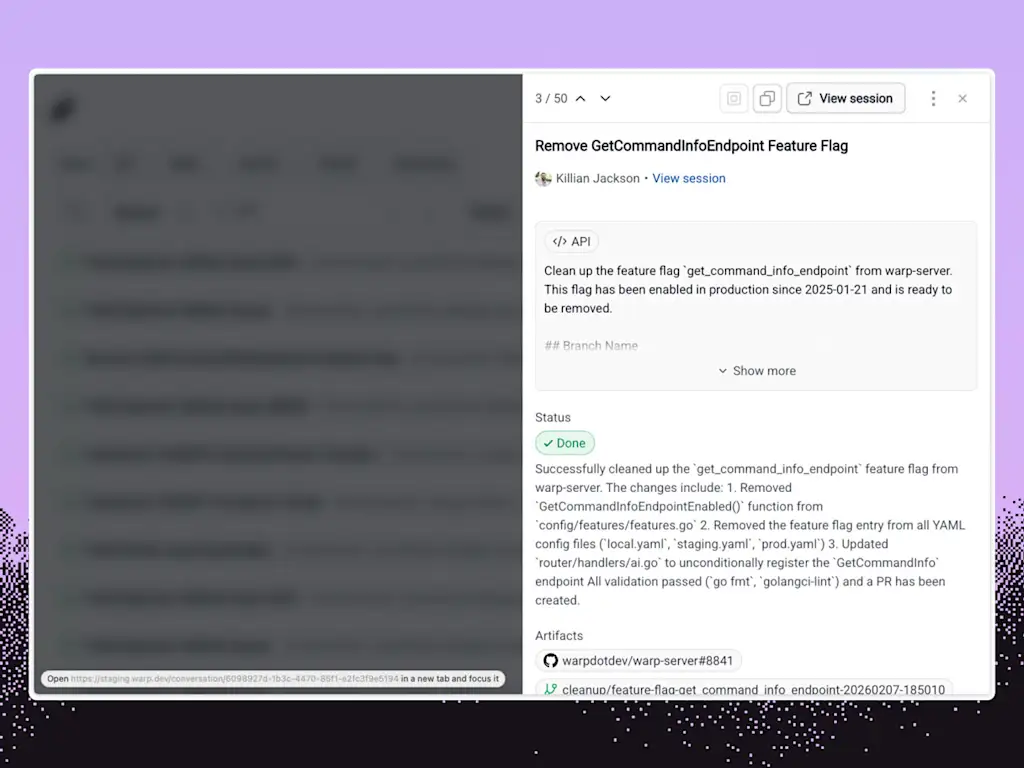

Warp unveils new software for collaborative AI coding

Warp, which builds software to help developers control AI agents and other software from the command line, is rolling out a new tool called Oz to collaboratively command AI in the cloud.

Last year, Warp launched its agentic development environment, which lets programmers command AI agents to write code and other tasks. Developers can also use the software to edit code on their own and run command-line development tools. That release came as many developers became increasingly fond of vibe coding—the process of instructing an AI on what source code should do rather than writing it directly—and the industry produced a variety of tools, including Anthropic’s Claude Code and Google’s Antigravity, aimed at assisting with the process.

But, says Warp’s founder and CEO Zach Lloyd, most existing agentic development software is geared at individual developers interacting with agents developing code on their own computers. That can make it difficult for teams to collaborate on agent-driven development and even make it hard for managers and colleagues to understand what individual developers already have AI agents working on. It can also make it difficult to guarantee agents are properly configured and securely handling company code and data, even in the face of deliberate attempts to steal data, like external “prompt injection” attacks meant to deceive AI, Lloyd says.

“Right now, with everyone who’s using these agents on their local machines, it’s like the Wild West,” he says. “You don’t know what they’re doing.”

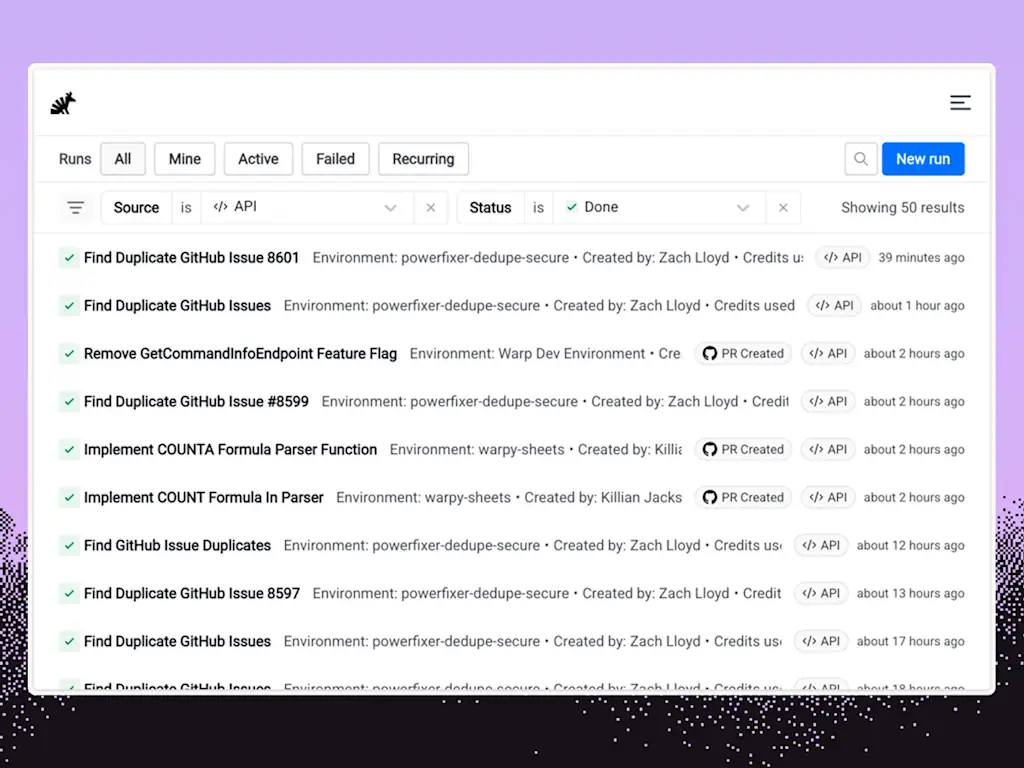

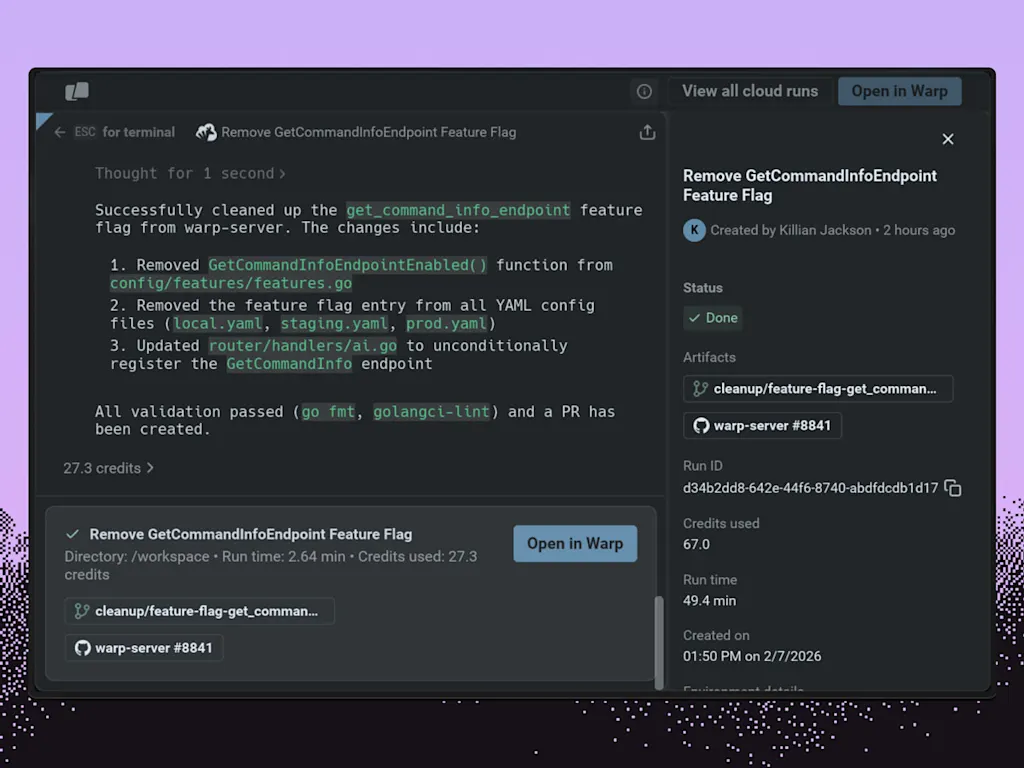

Oz looks to solve that problem by providing secure, cloud-based sandboxes for AI agents to run as they write code, process customer feedback and bug reports, and handle a variety of other tasks, with all of their operations logged and accessible through a Warp app or web interface.

“Every time an agent runs, you get a complete record of what it did,” Lloyd says.

Through Oz, companies can heavily customize what access employees have to different agents and tweak what permissions agents themselves have to avoid security risks. And agents can be automatically scheduled to run at particular times or in response to particular events, or manually instructed to run as needed, says Lloyd, demonstrating one agent the company uses internally to root out potential fraudulent use of its platform.

Developers can also switch between running particular agents in the cloud or on their own computers, which can be useful for interactive development, and the context of previous interactions and runs is automatically preserved. Since the cloud-based side of Oz is commanded via a standardized interface, locally run agents and other apps can even trigger agents to run in the cloud for purposes like generating code to respond to bug reports or feature requests.

“Our view on this is to try to make it really flexible, because companies are going to have lots of different systems and ways of deploying agents,” Lloyd says.

Warp says more than 700,000 developers are now using its software, which has expanded from an enhanced command-line terminal—the esoteric, text-based interface long beloved by power users on Linux and MacOS—to include tools for knowledge sharing and commanding AI agents. The company declined to share precise revenue numbers but said that annual recurring revenue grew by a factor of 35 last year.

Users of Oz will generally be charged both for cloud computing and for AI inference costs, with limited use of the system also available in Warp’s free plans, but customers can also work with Warp to use their existing infrastructure or AI models of their choice.

Warp, which reported at the end of last year that its agents have edited 3.2 billion lines of code, is in essence betting that even in an era when vibe coding is making it easier than ever to build custom software, companies interested in security, ease of use, and fast deployment will still prefer to use its tools for managing their coding agents rather than developing their own in house.

“Every company this year that’s building software is going to want some sort of solution to do this, just because it’s such a big potential force multiplier for how software is produced,” says Lloyd.