Category: Biometrics

Indonesia to ban under-16s from social media

Indonesia, the biggest country in Southeast Asia, is taking the momentous step to ban social media for under 16s. Communication and Digital Affairs Minister Meutya Hafid announced the new regulation on Friday.

“This means Indonesia is the first non-Western country to implement age-appropriate restrictions for children in the digital space,” she said in Bahasa Indonesian (English translation via Channel News Asia). Indonesia follows Australia in implementing such a law, while many other countries are considering it.

The minister cited increasing threats to children as the motivation behind the ban, mentioning exposure to porn, cyberbullying, online scams, and singling out addiction as the most important factor.

“The government is stepping in so that parents no longer have to fight the algorithm giants alone,” Hafid said during the televised address.

The ban begins March 28 with accounts for those aged under 16 on “high-risk platforms” to be deactivated starting from that date. Platforms prioritized under the ban will be Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X, Threads and YouTube. Livestreaming platform Bigo Live and video game platform Roblox were also highlighted by Hafid.

The minister framed the decision as taking back control and casting aside technology that may not prioritize people’s best interests. “We are taking this step to reclaim the sovereignty of our children’s future,” she said after recognizing the “inconvenience” that might be caused initially, following the ban.

“We want technology to humanize people, not sacrificing our children’s childhoods,” she concluded.

2025 law set the stage, Tony Allen briefs Indonesian gov’t on 27566-1

Last year, the Indonesian government brought in Regulation No.17 on the Governance of Electronic System Implementation in Child Protection. The regulation requires platforms and digital services to prioritize children’s safety, privacy and wellbeing through stronger safeguards, age-appropriate design and limits on harmful or exploitative practices.

Biometric Update reviewed the new regulation at the time, which frames age assurance as defense against child exploitation and targets platforms that are specifically intended for children. Since it includes social media and online games along with ecommerce platforms and streaming services, the broadness of the law could potentially mean additional platforms could eventually fall under the new regulation introduced on Friday.

Early last week, Indonesia’s Ministry of Communications and Digital Affairs undertook a surprise inspection of Meta Platforms’ Jakarta office, reports AP News. The inspection took place over concerns about Meta’s handling of harmful content on the company’s platforms including Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. Following the inspection, the ministry rebuked Meta for its improper compliance with national regulations.

As the individual who oversaw Australia’s Age Assurance Technology Trial (with Australia the first country to implement a children’s social media ban), and who helped author the international standard on age assurance, ISO/IEC 27566-1, Tony Allen knows about age assurance tech.

On LinkedIn, Allen revealed that he has met with the Indonesian minister. “It was a pleasure to meet with Minister Meutya Hafid on our recent visit to Jakarta with UK in Indonesia – British Embassy Jakarta,” he posted.

Allen said they’ve been assisting with briefings on the new ISO-IEC 27566-1 Age Assurance Systems Framework as well as the measures required to bring in highly effective age assurance measures for Indonesia.

The upcoming 2026 Global Age Assurance Standard Summit will feature an intensive master class on the ISO-IEC 27566-1 standard focused on practical implementation. Allen discussed the Summit, age assurance standards and more with the Biometric Update Podcast last week.

87% of failed biometric verifications in Southern Africa due to AI spoofing: Smile ID

A new report spotlights deepfake fraud posing an acute problem for Africa.

Digital identity, banking and e-government are being used to streamline and more efficiently facilitate financial inclusion and disbursement of funding, along with helping underserved communities access healthcare and other essential public services.

Smile ID’s 2026 Digital Identity Fraud Report has some jaw-dropping findings. In Southern Africa, almost nine in ten (87 percent) rejected biometric verification attempts were connected to AI-assisted impersonation and spoofing. The report says “fraud is overwhelmingly biometric in Southern Africa,” a region that encompasses countries including Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Meanwhile, Africa’s percentage of adults owning a financial account has risen from 34 percent to nearly 60 percent over the past decade. However, identity verification systems have largely stood still — tied to a one-time checkpoint model, Smile ID warns. Fraud has accelerated with the arrival of AI.

The figures were compiled from 200 million identity checks by Smile ID’s customer base across dozens of industries and 35 countries in 2025. The analysis covers the full identity lifecycle — onboarding, authentication, and high-risk account events — examining how fraud manifests at different stages of trust.

Smile ID found more than 160,000 fraudulent verification attempts in a single month in 2025, all of which were traced back to just 100 facial identities. “Some of these faces appeared over 12,000 times across multiple platforms,” the report says. Another case saw attackers use the same identity for more than a thousand account registration attempts within a space of 30 minutes.

“The most consequential fraud attacks today are targeted account takeovers (ATOs) — not fake IDs or isolated spoofs, but coordinated operations that compromise the capture pipeline, reuse real identities at scale, and exploit moments after approval when controls are lighter through highly scalable AI-powered tooling,” the reports claims.

This is a professionalized process with fraudsters coming in later in the customer journey, often colluding with insiders, and making use of large facial biometric and identity data sets. AI-powered tools are employed to analyze the data and to scale attacks. Generative AI has lowered the barriers to entry, reducing costs; creating high-quality synthetic documents and imagery while automating biometric manipulation, when this was previously uncommon or costly.

Now the cost of each try is marginal — approaching zero — attackers can reuse the same identity assets across hundreds of thousands attempts. Defenses built for a previous era are straining under the barrage. “Fraud defences must now assume abundance and use networked intelligence to spot patterns and turn the volume generated by fraudsters’ attacks against them,” the Smile ID report argues.

Smile ID discovered that nearly 90 percent of verifications rejected for suspected fraud in 2025 were found to be using mobile SDK integrations. This was up from 15 percent in 2023 and 65 percent in 2024. Mobile SDKs can capture additional on-device signals, such as image integrity and user behavior, that API-only verification flows cannot see. Biometric injection attacks have surged to over 100,000 per month, with Smile ID detecting the shadow of emulators, tampered capture and virtual cameras.

Continuously on defense and network intelligence

Mark Straub, CEO of Smile ID, comments that defense has to move beyond just the end of the pipeline. “Fraud is no longer a ‘KYC’ problem — it is a continuous cybersecurity challenge,” he says.

“Effective defence now requires network intelligence: By leveraging these privacy-preserving indicators throughout the customer lifecycle, we enable real-time adaptation. Identity has entered the security era, where eco-system wide protection is essential to safeguarding the individual,” he believes.

Modern fraud defense should operate across four interconnected zones, Smile ID argues, which form a continuous security infrastructure. These are trusted capture; verification and signal extraction; enforcement and feedback; intelligence and pattern detection, which all flow into another. Three strategic priorities build on this further.

Of these, priority two — harden authentication at high-value moments — is perhaps notable for its granular detail. For example, multi-factor authentication at high-risk moments, which in practical terms would mean requiring biometric verification in addition to OTP for password resets or device changes or high-value transactions.

The other two priorities are lifecycle intelligence, revealing where fraud will concentrate, and trusted capture, with capture integrity enabling richer signals. “Fraud now operates as repeatable, networked infrastructure,” the report concludes. “Defence must do the same.”

“This approach — a Network Defence — connects signals across the identity lifecycle, detects coordination that isolated systems miss, and strengthens with every verification.”

Smile ID’s 2026 Digital Identity Fraud in Africa Report can be downloaded here.

New York City lawmakers push sweeping restrictions on private sector biometric surveillance

New York City lawmakers are weighing a sweeping new attempt to curb the spread of biometric surveillance in everyday life, advancing legislation that would sharply restrict the ability of businesses and landlords to collect facial scans, voiceprints, fingerprints, and other uniquely identifying data from the public.

The proposals were the subject of a lengthy hearing this week before the City Council’s Committee on Technology where councilmembers, privacy advocates, and city officials debated whether biometric technologies have quietly expanded into retail stores and residential buildings with little oversight.

At issue were two bills that together would make New York City one of the most restrictive jurisdictions in the U.S. when it comes to private sector biometric surveillance.

The push reflects a growing concern among lawmakers that the technology has moved beyond narrowly defined security uses and is beginning to reshape the way businesses monitor customers and tenants.

Councilmember Shahana Hanif, the sponsor of one of the bills, argued that biometric identifiers present a fundamentally different privacy risk than ordinary data.

“You cannot cancel your face,” Hanif said during the hearing, emphasizing that biometric identifiers cannot be replaced once compromised.

The legislation responds in part to revelations that some retailers have begun experimenting with facial recognition systems designed to identify suspected shoplifters or repeat offenders.

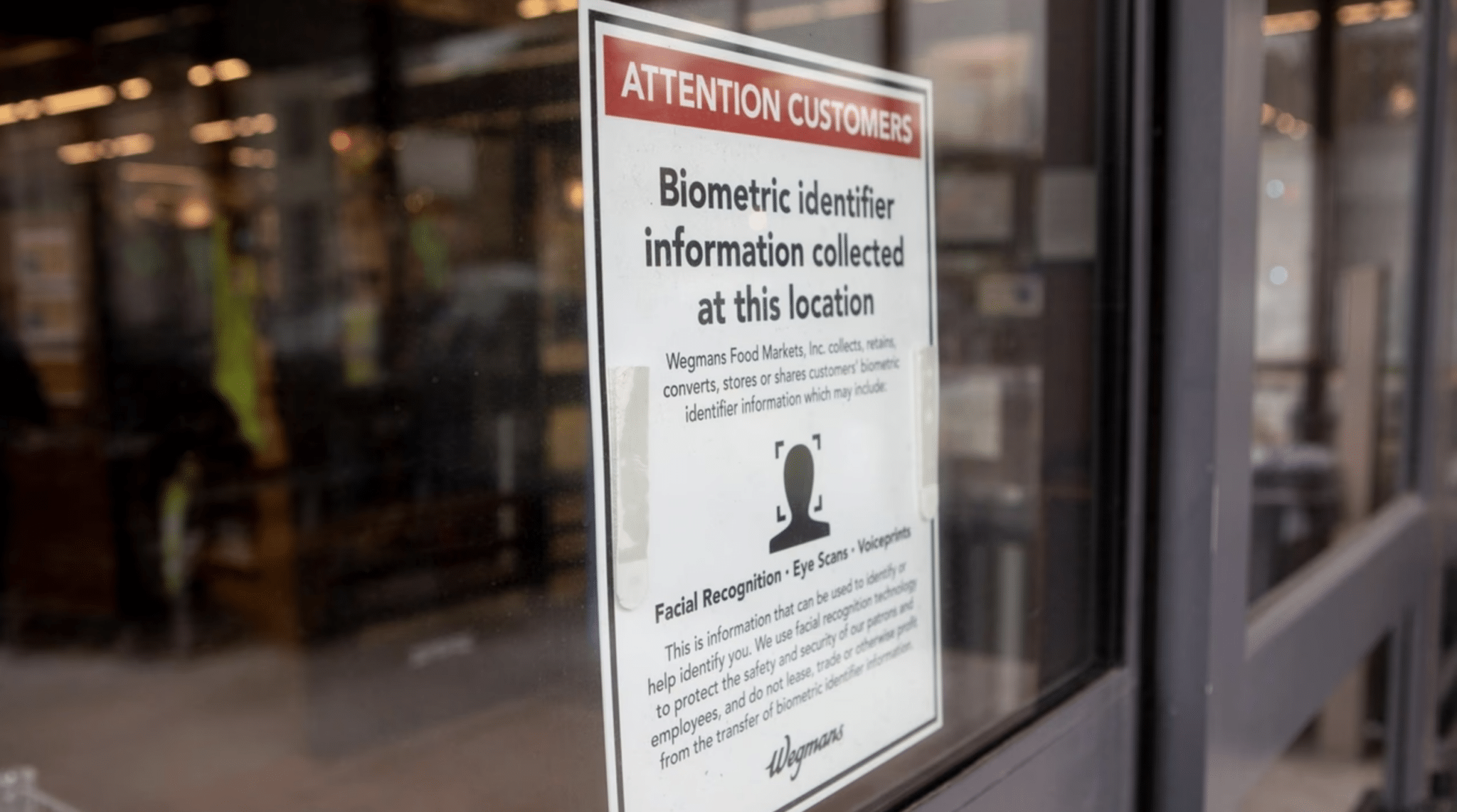

One example frequently cited by lawmakers involves grocery chain Wegmans, which has acknowledged using facial recognition technology in certain locations as part of its loss prevention strategy.

Under the first proposal, businesses that qualify as places of public accommodation would be barred from using biometric recognition technology to identify or verify customers.

The measure would go far beyond the city’s current rules, which mainly require businesses to post signs notifying customers if biometric information is being collected.

The bill would also expand how biometric identifiers are defined under city law. The definition would include not only fingerprints and iris scans but also voiceprints, facial geometry, and even movement patterns that could be used to identify an individual.

A second proposal introduced by Councilmember Pierina Ana Sanchez focuses on residential buildings. It would prohibit landlords from installing or using biometric recognition systems that identify tenants or their guests.

Lawmakers behind the measure say the growing use of facial recognition door entry systems in apartment buildings raises serious concerns about tenant privacy and potential surveillance inside private residences.

Together, the bills reflect a broader shift in the debate over biometric technology.

Earlier efforts in New York primarily focused on transparency, requiring businesses to disclose when they were collecting biometric data. The new proposals instead move toward outright prohibition.

Advocates for the legislation say that shift is necessary because disclosure alone has done little to slow adoption.

Civil liberties groups have warned for years that biometric surveillance systems can enable continuous tracking of people’s movements and associations.

Once deployed in retail stores or apartment buildings, they argue, such systems can quietly build databases of people who have done nothing wrong.

The debate gained additional momentum following several high-profile incidents in New York. In one widely publicized case, Madison Square Garden used facial recognition to identify and deny entry to lawyers affiliated with firms that were involved in litigation against the venue’s owner.

The incident highlighted how biometric tools could be used not just for security but also for private blacklisting.

At the same time, retailers have argued that biometric tools are becoming increasingly important for security as organized retail theft has grown more sophisticated.

Companies deploying the technology say facial recognition allows them to identify repeat offenders and prevent theft without requiring constant manual monitoring by security staff.

That argument did not persuade many councilmembers at the hearing, where lawmakers repeatedly pressed city officials and industry representatives about the risks of misidentification and data misuse.

The hearing also revealed gaps in the city’s own understanding of how biometric technologies are being used.

During testimony, representatives from the New York City Office of Technology and Innovation (OTI) acknowledged that the city does not maintain a comprehensive inventory of biometric data collection across agencies.

Alex Foard, OTI assistant commissioner of research and collaboration explained that the office only tracks certain technologies reported under Local Law 35, a 2022 New York City regulation requiring city agencies to annually disclose their use of automated, AI, or algorithmic tools that impact the public.

That disclosure system though does not capture every instance in which biometric data may be collected or stored. Some uses may fall outside the reporting framework, meaning that even city officials cannot fully account for how the technology is deployed across government.

“I do want to indicate that agencies could be using biometric data in ways that aren’t involved in algorithmic decision making or AI or other uses, in which case we would not have visibility into that collection,” Foard said.

The lack of clarity troubled several councilmembers, who argued that if the city government itself cannot fully track biometric technologies, it becomes even harder to regulate their use in the private sector.

The Office of Technology and Innovation did not take a formal position on the proposed bans but acknowledged the complexity of regulating rapidly evolving surveillance tools.

In written testimony submitted to the committee, the agency said it supports efforts to strengthen privacy protections while ensuring that legitimate uses of technology can still be evaluated carefully.

The debate also reflects a broader national trend. Across the U.S., lawmakers are grappling with how to regulate biometric systems that can identify people automatically through cameras, microphones, or other sensors.

Many of the existing laws focus on notice and consent requirements, requiring companies to disclose when biometric data is collected. Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act, for example, requires written consent before companies can gather biometric identifiers.

New York City already has a limited version of that approach. Current city law requires businesses that collect biometric information to notify customers through posted signs, but it does not prohibit the practice itself.

Supporters of the new legislation argue that those transparency requirements have proven insufficient. They point out that most consumers either do not notice the signs or do not understand the implications of biometric tracking systems that can log and analyze their movements across multiple visits.

Opponents, however, warn that an outright ban could create unintended consequences.

Retail industry groups say the technology can help prevent theft and improve security for both employees and customers. Landlords have also argued that biometric entry systems can be more secure than traditional key fobs or passcodes, which can easily be copied or shared.

Still, the political momentum in New York appears to be shifting toward stronger restrictions.

Privacy advocates argue that facial recognition and similar tools create the infrastructure for constant monitoring, allowing private actors to track people’s movements through stores, apartment buildings, and other everyday spaces.

For councilmembers pushing more restrictive legislation, the stakes are about more than just consumer privacy. They see biometric surveillance as a technology that could fundamentally alter the relationship between individuals and the spaces they inhabit, turning routine activities such as shopping or entering one’s apartment building into moments of automated identification.

Integrated Biometrics fingerprint scanners facilitate digital ID for inclusion in Ethiopia

Kojak fingerprint scanners from Integrated Biometrics are playing a major role in the enrollment of citizens for Ethiopia’s Fayda digital ID, in a move that is advancing digital inclusion of the country’s total population.

Since 2023, Ethiopia has been implementing the Digital ID for Inclusion and Services Project with funding from the World Bank.

More than 30 million people have so far been registered for the ID initiative, with a plan by the Ethiopia National Identity Program (NIDP) to reach 90 million people by the end of 2027. Over 90 agencies have also integrated their services with the digital ID system, making identity verification and authentication easier.

Integrated Biometrics is one of the technology partners supporting the project, and the U.S. firm says in a case study that NIDP is using its Kojak scanner for fingerprint capture during identity enrollment. The scanner is MOSIP-compliant.

“This lightweight scanner (725 grams) rapidly collects prints from dry fingers and can operate in direct sunlight and extreme temperatures. With very low power consumption, the registration kit can operate for lengthy periods of time without an electrical connection,” the company writes, adding that to reach NIDP’s enrollment target, the durability of Kojak scanners, “which exceeds US military standards, is critical.”

The case study recalls the challenges Ethiopians faced having to access public services without a legal or digital identity in the past. It notes that the Fayda digital ID does not only facilitate access to a wide range of services, but is also an important tool to support Ethiopia’s 2030 digital transformation strategy and digital economy growth.

The characteristics of the scanners, according to Integrated Biometrics, is contributing to the success rate of Fayda enrollment as it makes it possible for NIDP to “enroll participants as close as possible to their homes, increasing the likelihood of successful registration.”

Efforts are also being multiplied by the government to make sure the national digital ID is issued to refugees to give them a sense of inclusion in the Ethiopian society, something the UNHCR lauded early this year.

With the Fayda digital ID, Ethiopians now easily have access to a wide range of services from public institutions and the private sector.

In the capital Addis Ababa, the Fayda has been linked with the city’s residency card system, which means that residents no longer need to submit biometrics anew when applying for a residency card, according to Addis Fortune.

There’s also a policy from the country’s central bank for all commercial banks in the country to integrate customer accounts with their Fayda ID details, and the official deadline for the directive to be fully complied with is March 30.

Online dating at risk as romance scams, deepfakes infiltrate platforms

Online dating sites are being flooded with deepfakes and AI content, making it hard for users to distinguish real matches from fraud bots. At the same time, some users are discovering that a corporeal body is more of a “nice to have,” as they turn to AI companions generated by large language models (LLM) over flesh-and-blood partners.

New data from Sumsub shows that so-called “romanceslop” is souring the experience for many users, resulting in what a release the biometrics and anti-fraud firm describes as a hollowing-out of once useful apps. Thirty percent of those who participated in a survey say their dating experience has been “negatively affected by receiving AI-generated content.” Sixty-one percent have already been deceived by fake profiles, or know someone who has, and 84 percent say “deepfaked catfishes and AI content have made it harder to trust people or date successfully.”

Identity fraud is rampant in the online dating world. Recent research shows that 61 percent of people that have used dating apps or websites in the UK have matched with a profile they later discovered, (or strongly suspected) was a bot, scammer or catfish. It’s just as bad across the pond; a report from Politico cites FBI data showing that Americans lost more than $16 billion to cybercrime, including romance scams, in 2024.

Sumsub says “modern widespread and powerful AI tools, like Google’s Nano Banana, have given experienced online fraudsters the means to almost perfect messages and images that can deceive even the savviest romantic.”

Shall I compare thee to an LLM? 36% say yes

Some might worry AI is spoiling love, but others are embracing it. Among the 2000 UK-based respondents, 36 percent have used an AI companion as an alternative to dating apps – and 50 percent of all women are open to the idea.

Meanwhile, 32 percent use AI tools as a dating coach or to write messages. So even for those who aren’t giving their heart to Claude, LLMs are serving as virtual Cupids who can guide them in matters of the heart. As far as profiles go, 60 percent of users believe “some AI-altered content should be allowed” on dating platforms – but 42 percent “have zero tolerance for any image alterations.”

Sumsub notes the paradox at play: “adoption of AI features is growing steadily even as trust and confidence falls.” Regardless, however you slice it, online dating has fundamentally changed.

What hasn’t is the desire for a safe and secure online experience. Eighty one percent of respondents believe dating platforms should be held responsible for malicious content hosted on their platforms. “The imperative on dating apps is clear,” Sumsub says. “Govern AI content to protect online daters, or scramble to react when bad actors cause serious harm.”

Get safe or become obsolete: Sumsub

“Platforms have a clear responsibility to protect users without restricting how they choose to engage online,” says Nikita Marshalkin, head of machine learning at Sumsub. The company has found that many users are willing to accept AI-enhanced dating experiences with appropriate guardrails in place – which means it’s critical how those guardrails are managed.

“Users can’t be blamed for using AI features offered to them, nor can they be expected to manage the resulting wave of AI content without support.” Marshalkin says. “A blanket ban isn’t the answer, but without exhaustive governance and improved user awareness around deepfakes and misleading content, online dating will soon become more trouble than it’s worth.”

“The response from the dating industry is going to be watched very closely by businesses in other sectors who are waking up to how basic verification checks can’t compete with the increasingly sophisticated methods scammers use today.”

Gen Z showing increased preference for in-person dates

Gen Z, as it turns out, is getting wise to the risks associated with online dating, and opting to try and find romance face-to-face. New data from Barclays shows that, with seven in 10 (67 percent) of reports of romance scams originating on dating sites and social media platforms in 2025, 56 percent of Gen Z singles are now prioritizing meeting a partner in-person.

“One in two Gen Z singletons say AI scam concerns have changed how they date online – almost double the 25 per cent national average,” the research says. “In an apparent reversal of a trend towards dating apps in recent years, 56 per cent of Gen Z singles say they’re focusing on meeting a partner in real life, rather than via online dating – significantly higher than the 42 per cent average across generations.”

DHS signals major expansion of biometric matching infrastructure

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has issued a Request for Information (RFI) seeking industry input on biometric matching software capable of operating across all major DHS components.

The RFI signals a department wide effort to standardize and scale biometric matching capabilities across Customs and Border Protection, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Transportation Security Administration, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Secret Service, and headquarters elements.

At its core, DHS is seeking a single scalable software capability that can handle mission critical identity verification, vetting, and investigative operations under an enterprise license structure.

Taken together, the RFI and accompanying documents outline a sweeping modernization effort aimed at consolidating and scaling biometric matching across the department. DHS is effectively mapping out a lifecycle management framework that extends from initial award through ongoing performance assessment.

If DHS proceeds to a formal solicitation, the resulting contract would shape how identity verification, watchlist screening, fraud detection, and investigative matching are performed across some of the most security sensitive missions in the federal government.

For industry, the RFI is an invitation to demonstrate not only algorithmic performance but architectural maturity, compliance depth, and governance alignment.

For policymakers and civil liberties observers, it signals a continued expansion and integration of biometric infrastructure within DHS, albeit under tighter data ownership, portability, and audit controls than have characterized some earlier deployments.

According to the draft Statement of Work attached to the RFI, DHS requires an enterprise level, scalable, and secure biometric matching software solution that can seamlessly integrate with other biometric systems already operating within the department.

The objective is not simply to purchase software licenses but to define requirements, deliverables, scope, and performance expectations for a department wide solution that includes integration, testing, documentation, training, and sustainment.

The envisioned system must support multimodal biometric inputs. The draft requirements specify facial recognition, fingerprint and palm print matching, iris recognition, voiceprint matching where applicable, and biographic matching augmentation.

DHS expects both real time and batch matching capabilities, support for search and identification workflows, configurable watchlists, deduplication functions, and adjustable scoring thresholds.

The software must meet defined performance standards for false accept and false reject rates while maintaining high throughput and low latency in high volume environments.

Performance is a central theme throughout the RFI. DHS emphasizes that vendors must demonstrate the ability to support large scale 1 to 1 verification and 1 to N identification searches with strict latency targets and uptime service level agreements.

The department is asking for empirical evidence drawn from operational deployments or government relevant testing environments rather than relying solely on vendor laboratory claims. In effect, DHS is signaling that any future award will hinge on demonstrated operational maturity.

Security and privacy requirements are equally prominent. The draft Statement of Work requires compliance with federal, state, and international privacy and data protection frameworks and DHS privacy directives, along with alignment to ISO biometric performance and presentation attack detection standards.

Encryption of biometric data at rest and in transit, role-based access controls, secure key management, and integration with DHS security monitoring tools are mandatory features.

Auditability and oversight are embedded into the technical requirements. The solution must generate comprehensive logs covering enrollment, matching transactions, administrative actions, configuration changes, access attempts, and data exports, and must integrate with DHS approved Security Information and Event Management platforms such as Splunk, QRadar, or Elastic.

These provisions underscore that DHS views biometric matching as a mission critical capability that must withstand continuous security review and forensic scrutiny.

Data governance and ownership provisions are unusually explicit. The government will retain exclusive ownership over all raw biometric data, templates, metadata, matching results, audit logs, and performance data generated during operations.

Contractors are prohibited from asserting ownership or reuse rights over government data and may not use DHS biometric data for algorithm training or commercial improvement without written authorization.

The RFI explicitly notes that biometric data must remain the exclusive property of the government and that the enterprise license must permit broad use across DHS components and operational environments.

These clauses directly address long standing concerns about vendor use of government biometric datasets for proprietary model enhancement. They also reflect an intent to avoid fragmented component level licensing arrangements and to consolidate biometric matching capabilities under a single contractual umbrella.

The RFI also reflects a strong emphasis on portability and exit rights. Vendors must ensure that all government data can be exported in nonproprietary or standards-based formats to support migration, archival, independent testing, or vendor transition at contract expiration.

In a market often criticized for vendor lock in, DHS is clearly seeking architectural and contractual safeguards to preserve flexibility.

Deployment flexibility is defining feature of the requirement. The system must support on premises, cloud-based, hybrid, and optional edge deployments, and must accommodate elastic scaling and capacity growth over a three to five year horizon without major architectural redesign.

Vendors are asked to detail supported biometric modalities, demonstrated performance metrics, interoperability strategies, and approaches to minimizing vendor lock in.

They must also explain encryption methods, access control models, audit capabilities, compliance certifications, and policies governing the use of government data.

Finally, they are required to address sustainment models, disaster recovery architectures, licensing structures, and experience supporting proof of concept evaluations and integration testing.